There are a lot of layers to democratisation, but most simply put we mean that the technology has improved to the point where powerful enough sensors, as well as software, are becoming cheaper and allowing more organizations access to this technology. Often, the talk of democratised reality capture points back to traditional industries. But really, it helps society as a whole.

Original Source - GEO Week News

That can mean different things for different use cases, of course, ranging from some use cases being accessible simply with the lidar sensors now included on the back of iPhones, to the most powerful terrestrial scanners coming in at lower price points.

For the most part, the conversations around this democratisation revolve around the surveying and AEC industries, and for completely valid reasons. These are the industries that most benefit from this technology, and opening up powerful technologies for those outside of the top of the space is healthy for the industry as a whole. Construction, for example, has long been seen as averse to new technology, and price is one of the reasons. Now that more firms can more easily access these tools, efficiency for the entire industry rises.

It’s not just those traditional industries that benefit from this democratisation, though. In fact, one could argue that we all do.

As someone who covers a wide range of technologies and use cases, much of which revolves around reality capture in some way, shape, or form, among my favorite broad topics is historical preservation. It’s not the first use case we generally think of with regards to laser scanning – or photogrammetry, for that matter – but it’s an incredibly important use case culturally, and one that has also benefited significantly from this democratisation process.

We’ve talked briefly about some examples showcasing what increased accessibility looks like with things like traditional scanners becoming cheaper and good-enough (and improving) scanners being added to the most popular smartphones on the market, but that doesn’t even cover the full breadth of this trend. We’re also talking about greater accessibility to complementary hardware, like UAVs, as well as simpler and/or cheaper software to take the collected data and turn it into something usable.

In terms of preserving important historical structures, what this means is that more organisations and individuals are able to participate in making sure these buildings are properly recorded. No longer is it necessary to have the full financial backing of a massive and deep-pocketed company, nor does one have to be extremely technical. More people are able to capture this data, and more of our history is preserved digitally.

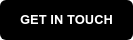

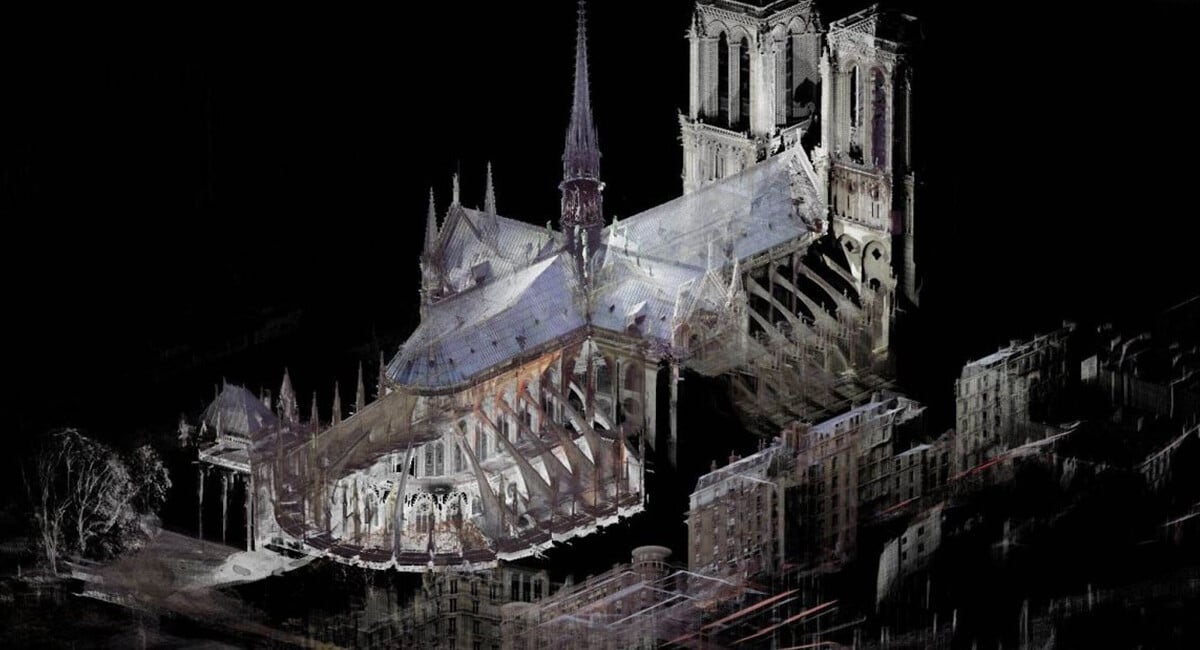

I think immediately of an article written by our Carla Lauter in the summer of 2022, highlighting this kind of work done in Ukraine to preserve buildings that could be potentially destroyed in the war with Russia. Or the group that worked to digitally preserve a historic ghost town in California. Or how this kind of digital preservation helped the process of rebuilding the Notre Dame cathedral after a devastating fire in 2019. Not all of these specific projects were opened up thanks to this increased accessibility, but it demonstrates the power of this work in general.

There’s a few different ways that the data collected from these historic structures are used. Most obviously, as in the case of Notre Dame, is as a template for rebuilding immediately. In this case, scans were completed in 2010, providing a crucial database for the builders tasked with rebuilding this iconic religious structure.

In the case of Ukraine, meanwhile, they acknowledged that it was unlikely the funding for rebuilding would be available immediately after the war. However, these scans will provide the blueprint for future generations if and when they are able to rebuild. Or, there’s the case of the ghost town, which views these 3D models as a way for future generations to experience this area even when it’s gone through digital means, potentially even from the other side of the globe.

Think about all of the structures that have been built throughout our history for which there are absolutely no records and it becomes clear how valuable this work can be. It’s unrealistic to think that we could – or would even want to – rebuild all structures, or even all structures that we currently think are important. New structures will come in, and old ones will be cleared for more green space. But that digital record will always be key for future generations to have as full a picture as possible about what society is like at any given time, and the fact that we now have more people and organisations who will have the ability to collect this data is an undeniable positive for our society today and moving forward.